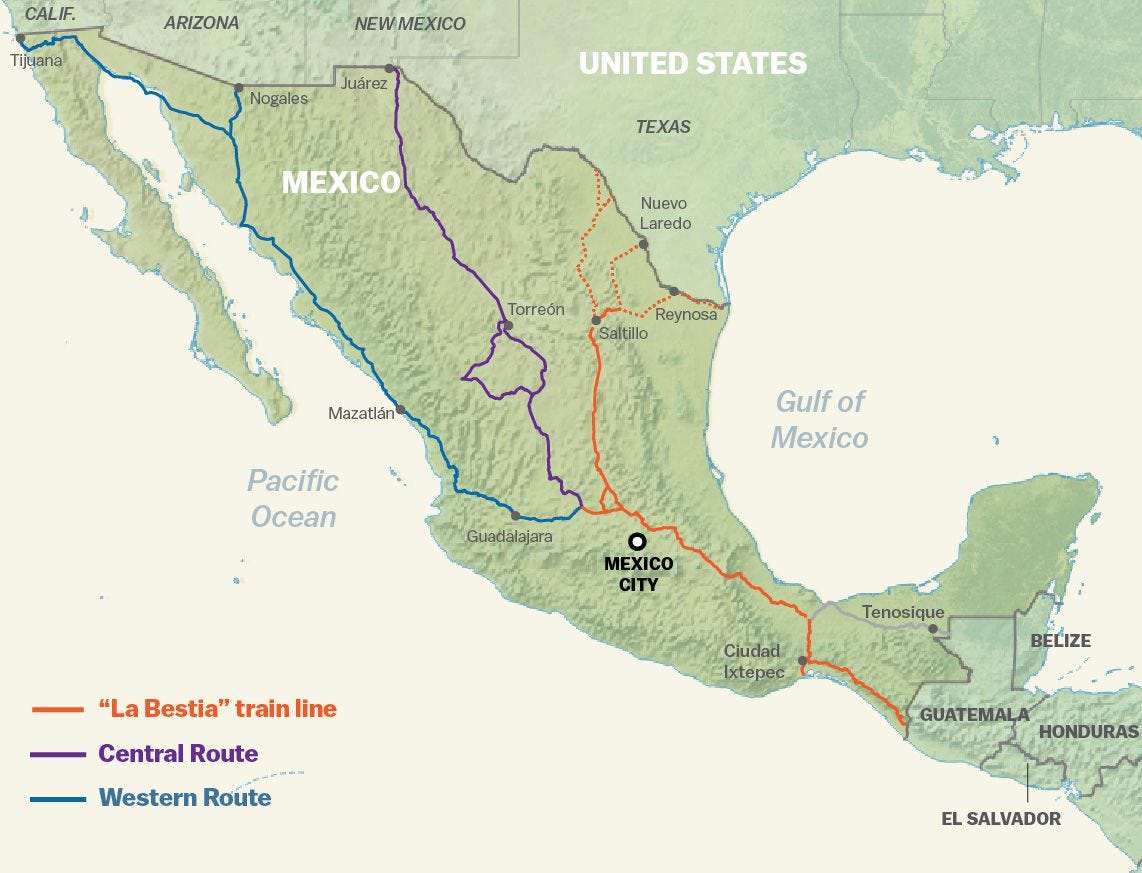

Mexico was considered the worldwide largest “bilateral corridor” to reach the United States (United Nations, 2017). A classic example of this is ‘La Caravana del Viacrucis Migrante’ comprised of immigrants coming from the Northern Triangle of Central America (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras) that were escaping from political instability, economic crisis and high rates of violence in their home countries. According to the Migrant Institute of Jalisco (2018), in March 2018 there were around 1, 500 immigrants trying to cross the border to the United States passing by Mexico. However, due to difficult circumstances along the way, a smaller group of around 600 people made it to the north of Mexico. To reassure no one migrate in an irregularly manner, the United States militarized its border, potentially violating the prohibition of collective expulsions (see Art. 22.9 of the American Convention on Human Rights “Pact of San Jose, Costa Rica”). Many actors were involved in this phenomenon, from public institutions to civil society organisations contributed to the wellbeing of immigrants, providing food, water and medicines, and most important, monitoring the violation of human rights in their arduous journey. For instance, NGOs were pivotal to monitor living conditions and safety of this immigrant group. Demographic characteristics showed that around 101 kids under 12 years old, 86 adolescents between 13 to 18 years old, 419 adults, and 9 elderly people were part of this migrant “Caravana” (Migrant Institute of Jalisco, 2018). A considerable part of the group were kids who were exposed to different traumas.

129, 163, 276 in 2017

1, 224, 000 in 2017

0.9 percentage of total population in 2017

Umbrella term that covers labour migrants and refugees. According to the OHCHR (2016), migrants in transit risk a range of human rights violations and abuses.

Someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war or violence (UNHCR, 2019)

When people flee their own country and seek sanctuary in another country, they apply for asylum (UNHCR, 2019)

Title:

Main nationalities and migration drivers

Result:

♦ Economic Migrants

⇒Number:

Around 250, 000 apprehension of transit migrants who travel in an irregular manner.

For at least two decades, tens of thousands of people from the Northern Triangle have traveled annually through Mexico to reach the United States (see Annex 1).

⇒Nationalities:

Transit migrants coming from Central America headed to the United States, with emphasis in the “North Triangle” cone:

National- origin composition of undocumented border crossers in 2014:

♦ Refugees and Asylum Seekers:

⇒Number:

Almost 30, 000 asylum seeker requests, of which 10, 000- 15, 000 are pending solutions in 2018. (See annex 2).

⇒Nationalities:

El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. More recently, also Venezuelans. (Migration Policy Institute, 2019).

♦ Migration drivers to economic migrants, refugees and asylum seekers:

Source

_________________________________________

Title:

Legislation

Result:

♦ Federal level

♦ State level

Sources:

_________________________________________

Title:

Main current challenges related to transit migration

Result:

♦ Common to economic migrants, refugee & asylum seekers:

♦ Specifically to refugees and asylum seekers:

♦ Development (cross-cutting) issues:

Sources:

Observation

Disclaimer:

This information does not reflect the total of programmes implemented during the current or past administrations. It only shows the data publicly available on internet. Hence, information may vary.

Federal level Institutions:

Official (government) responses to transit migration:

I. Current government administration (from enforcement to protection):

♦ Special programs for refugees and asylum seekers

II. Past government administrations

Observation:

Disclaimer:

This information does not reflect the total of programmes implemented during the current or past administrations. It only shows the data publicly available on internet. Hence, information may vary.

Local Government:

Municipal Governments for the three routes: Western, central and east/train line.

Official (government) responses to transit migration

♦ Economic migrants, refugees and asylum seekers

♦ Refugee and asylum seekers:

Information collected from Robert Strauss Center and Center for U.S. Mexican Studies (2019).

⇒East/train line route:

⇒ Central route:

⇒Western route:

Source: Robert Strauss Center and Center for U.S. Mexican Studies (2019)

Observations:

Disclaimer:

This information does not reflect the total of programmes implemented. It only shows the data publicly available on internet. Hence, information may vary.

Institution:

♦ Think tanks

I. Red de Documentación de las Organizaciones Defensoras de Migrantes (REDODEM):

Description:

REDODEM gathers civil society institutions that are dedicated to the attention of migrants in transit, generating annual reports which shed light on the routes used by migrants and the different violations of human rights during their journeys. REDODEM is comprised of the following organizations:

Non-State Actor responses to transit migration

REDODEM has carried out important investigations in the following thematic areas:

II. Migration Policy Institute:

Description:

Founded in 2001, the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) has established itself as a leading institution in the field of migration policy and as a source of authoritative research, learning opportunities, and new policy ideas.

To support this, the Migration Policy Institute:

Develops innovative policy ideas to address immigration and integration challenges more effectively.

Non-State Actor responses to transit migration:

_________________________________________

♦ Academia

I. Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, UNAMDescription:

Critically review legal research practices, in order to promote up-to-date research. For this endeavour, this Institute focuses on the following programmatic areas:

1) Diagnosis of the quality of the research;

2) Tools for epistemological, theoretical and methodological innovation in legal research;

3) New ways of teaching legal research.

Non-State Actor responses to transit migration:

One of its main research focus is migration. Through an online portal, this Institution has created a directory of NGOs that can provide support to migrants. This information is geographically divided by States:

https://migrante.juridicas.unam.mx/es/directorio/ong%27s

II. Robert Strauss Center for International Security and Law

Description:

This Center integrates expertise from across the University of Texas at Austin, as well as from the private and public sectors, in pursuit of practical solutions to emerging international challenges.

Non-State Actor responses to transit migration:

* Information collected from Robert Strauss Center and Center for U.S. Mexican Studies (2019).

⇒East/train line route:

⇒Central route:

⇒Western route:

In Tijuana, Baja California. Every day, between 40 and 180 asylum seekers add themselves to the waiting list. Over the past several months, the times when asylum seekers can add themselves to the waitlist has decreased from four hours to two.10 A volunteer has created a website for the list (elnumerodelalista.com) so that asylum seekers can track the waitlist numbers without having to travel daily to the port of entry, where the latest number is posted.

III. Colegio de frontera norte

Description:

Dedicated to high level research and teaching. Its main purpose is to:

Non-State Actor responses to transit migration:

_________________________________________

♦ Churches

I. Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes- México

Description:

Non-governmental, humanitarian and non-profit organization that seeks to reduce the vulnerability of migrants.

Non-State Actor responses to transit migration:

⇒Projects in Communities of Origin and Transit

⇒ Cross-cutting projects